You may not have seen it on the news, but last Wednesday, the new UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer traveled to Brussels to meet Ursula Von Der Leyen, Charles Michel and Roberta Metsola, respectively the presidents of the EU Commission, European Council and EU Parliament.

It was the first official visit to the EU institutions in Brussels for the UK Prime Minister, and as such, it was an important test of the much-hyped “European reset” of the new UK government following the catastrophic demise of the Tories in the last UK general elections.

Yet, part of the reason the meeting didn’t seem very newsworthy was precisely the lack of…well, news. Neither the press conference following the discussions nor the joint statement from Starmer and Von Der Leyen provided journalists with details about what this “reset” might actually look like.

The only clear outcome of the meeting was that other meetings would follow, hence its description as “a meeting about a meeting” and what appears to be the beginning of yet another phase of neverending Brexit negotiations – a defining feature of recent Tory governments that could come to characterize the new Labour premiership as well.

What’s worse, Starmer’s obstinate refusal to even contemplate proposals for a youth mobility scheme with the EU – similar to those the UK already has with countries such as Australia, New Zealand but also San Marino and Andorra – left many EU officials bewildered about the true intentions of Starmer’s European policy.

What does he really mean by his European reset? And is his main mission really to “Make Brexit Work,” as he first put it in a speech two years ago?

These questions were at the core of the event we hosted last Thursday on our Youtube channel. If you missed it or want to re-watch it you can do so by clicking on the image below.

This intriguing discussion between Scottish EU expert Kirsty Hughes and English writer and founder of our campaign Anthony Barnett unveiled the deeper rationale behind Starmer’s European strategy.

Hughes described it as “extremely minimalistic, adopting most of Boris Johnson Brexit red lines,” emphasizing how “if he was ever going to be brave about the EU, surely it would be at the start, when he has five years to go.” This is a sentiment we share, and it hardly inspires optimism about the future of UK-EU relations.

Barnett, on the other hand, is convinced that at a fundamental level, Starmer’s team has decided to make Brexit work because they don’t think the UK will ever be ready to rejoin as a normal European country. Instead, they would rather think of the UK’s core identity as being “an arm of the greater American hegemony.”

Our distinguished guests also discussed the prospect for Europe, the UK and Scotland in the event of a potential return of Donald Trump, as well as the recent general elections in the UK. As Barnett put it, “there is a very wide sense that there is something illegitimate about this government, the size of its majority and the power it can exercise.”

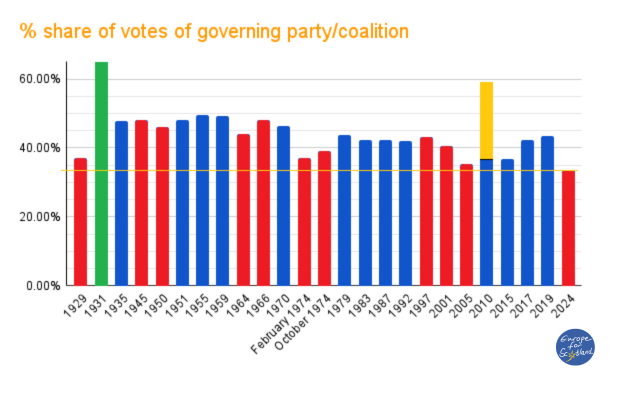

Percentage of share of votes of parties winning government in UK elections since the introduction of universal suffrage (1929). Colors denote the winning parties: Labour (red), Tories (blue) Libdems (yellow) or national coalition (green). Starmer’s government has the weakest democratic mandate in the history of UK democracy. Data and graphics from Europe for Scotland.

For her part, Hughes noted that the government “didn’t seem to have a plan for its first 100 days,” which have been marked by a staggering series of missteps, including the so called “freebie-gate” scandal over the enormous amount of freebies received by Starmer, bitter internal rows, and controversial political decisions such as cutting heating subsidies for pensioners. Importantly, from our standpoint, Hughes highlighted how the main UK parties’ silence on Brexit further reinforces “the disconnect between politics in Scotland and in Westminster” – an observation followed by a lively discussion over the history and the future of Scottish politics under Starmer’s government.

Differences between percentage of votes and percentage of seats in UK General elections.

Ultimately, a government that rests on the lowest level of democratic support since the introduction of universal suffrage in the UK does not seem to have the trust of many people in England, let alone in Scotland and across the UK. Trust is an important asset of any negotiation. And if England and the UK cannot trust him, the question surely stands: can Europe trust Starmer?

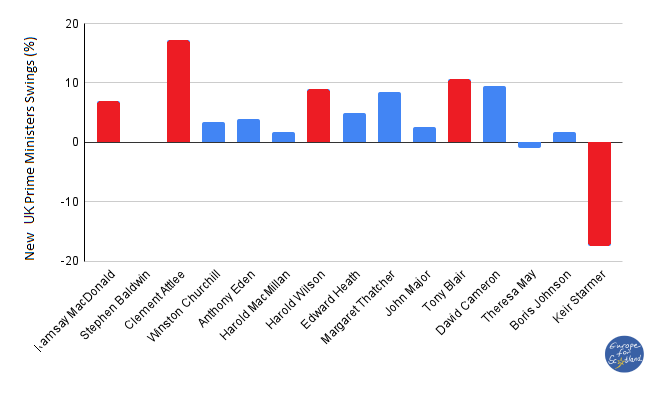

Swing of UK new Prime Ministers in their own constituency in UK General elections. Note that Stephen Baldwin was elected unopposed in his Bewdley seat in the election of 1924, 1931 and 1935. Keir Starmer has the worst ever record with a net −17.4%. Data and graphics from Europe for Scotland.