How the UK voting system produces inequality: why inequality is spiralling out of control under the UK’s electoral rules

guest article by Stuart Donald

Many think that the UK electoral framework, called “First Past the Post” (FPTP) is bad because it is less democratic than Proportional Representation (PR). However, talking about the electoral system can feel dull for anyone but political geeks and it is never really a priority for governments against health, education etc. But data now emerging shows that since 1980, the electoral mechanism is in fact a core reason why the UK is in a far worse state than its mainland peers; it leaves no doubt that FPTP is a trap which is driving the inequality gap ever wider. Let’s see why.

- It all starts with the absurd winner-takes-all element in the FPTP mechanism…

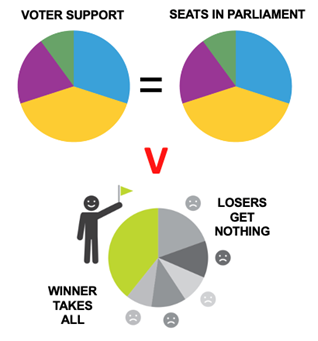

Let’s start with some UK electoral system 101: the country is split into 650 electoral constituencies, each electing only one MP. All parties stand one candidate each. Each voter chooses only one of these candidates. The one that gets the most votes, is elected, irrespective of any other consideration such as the total number of votes he or she gets, or the percentage share. Only the first gets ‘past the post’ so to speak. If you vote for any other candidate than the winner, your vote is wasted and will not count towards the election of an MP.

Absurd indeed. It almost feels inappropriate that a term borrowed from the card game rooms of Las Vegas

should apply in any way to democracy. Yet it’s true; in the UK, if you vote for the wrong party, that is, anyone other than the one with the most votes in your constituency, your vote simply will not count. This is unlike Proportional Representation (PR) electoral systems where all votes have an impact and as long as a party gets more than the minimum threshold, your vote will influence who gets to parliament. Why is this important? How can this really make a difference?

2. ‘Winner-takes-all’ makes the FPTP election a ‘two-horse-race’

Typically, Anglo-Saxon democracies like the UK, Canada, Australia[1] and the US , have only 2 parties involved in government. Why is that? Because the voters have learned how the ‘winner-takes-all’

outcome works; they know if they want their votes to count, they need to anticipate who will win. That drives the race down in all cases to two horses – the lowest level to allow the voting strategy any chance of working. So voters vote tactically between the two anticipated leading horses, eliminating all others from the contest. But again, what is wrong with this? Still democracy, right?

outcome works; they know if they want their votes to count, they need to anticipate who will win. That drives the race down in all cases to two horses – the lowest level to allow the voting strategy any chance of working. So voters vote tactically between the two anticipated leading horses, eliminating all others from the contest. But again, what is wrong with this? Still democracy, right?

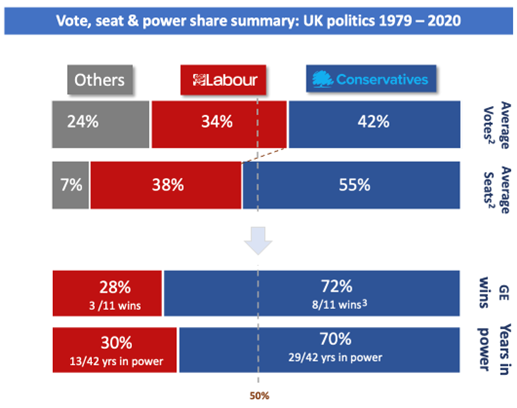

3. The FPTP mechanism rewards winning parties with more seats than their votes merit – In the UK the Tories won 8 of the last 11 elections since 1980 achieving on average 42% of the vote[2]. In all cases they had won a minority of votes. If the UK had a PR electoral system they’d have had to form a coalition to govern and negotiate with other parties, ensuring some tempering of their agenda. As a result, the shape of policy would have been very different (for instance, a coalition government would have negotiated a much softer Brexit than the extreme version the Tories delivered in 2019). But here’s where FPTP is properly bonkers; because Tory votes are typically more evenly dispersed across the UK than Labour’s, the winner takes all mechanism allocates many more seats to the Tories than their vote share merits. As shown here, on average this resulted in 55% of all seats, a stonking 40+ seat average majority, despite winning only 42% of votes. And the exaggeration of Tory power gets even more absurd; winning 8[3] of the 11 elections since 1980, accounting for 70% of government time. Is this really democracy?

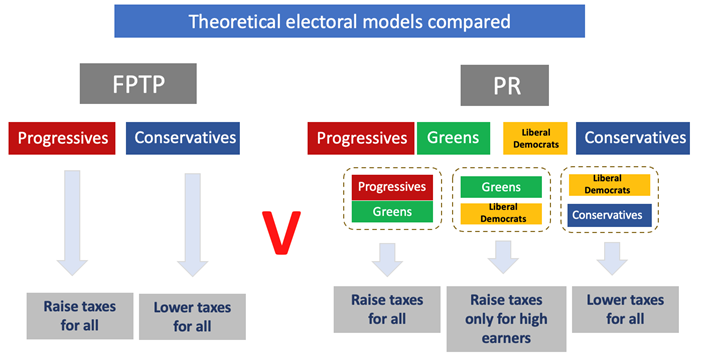

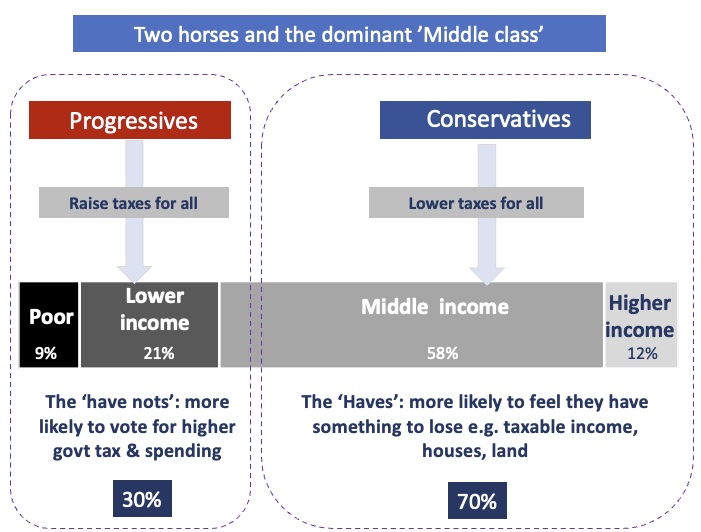

- Binary ‘2 horse’ race makes FPTP policy outcomes far less ‘nuanced’ than under more ‘pluralist’ PR – if there are only two possible outcomes, there can be only two broad communities or coalitions of voters for the parties to appeal to. Countries with an electoral system based on proportional representation, on the other hand, offer a wide range of credible, electable options across at least 4 parties, offering way more viable coalition propositions between them. That means parties can appeal to more focussed sections of the electorate, e.g. progressives, greens and the could aim to attract poorer, lower and middle income voters with a coalition promise to raise taxes only for the upper middle and high income earners. But back in FPTP land, if you have to appeal to all sections of the income spectrum, you can’t risk a policy like this!

- The ‘haves’ outnumber the ‘have-nots’ by more than 2 to 1 giving their horse an edge in the race – over the last 50 years, the ‘haves’ – defined as those that enjoy higher than the median level of income – have represented around 70% of developed country electorates. They are obviously not an organised group of voters, but they all have one thing in common; they have something to lose. Many of them will not welcome a government that might raise taxes, spend money on things the ‘haves’ don’t think they need and otherwise meddle unhelpfully. Obviously, not all ‘haves’ will vote the same way, but their sheer numbers mean that the things they hold in common will be central to what policies are taken forward.

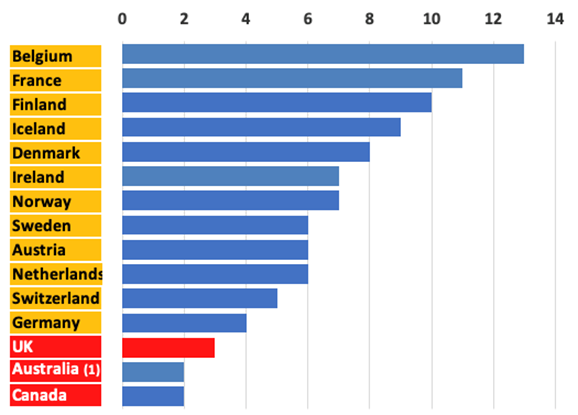

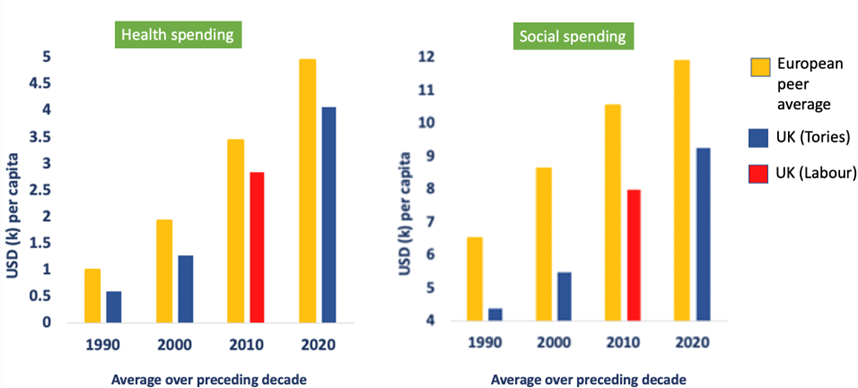

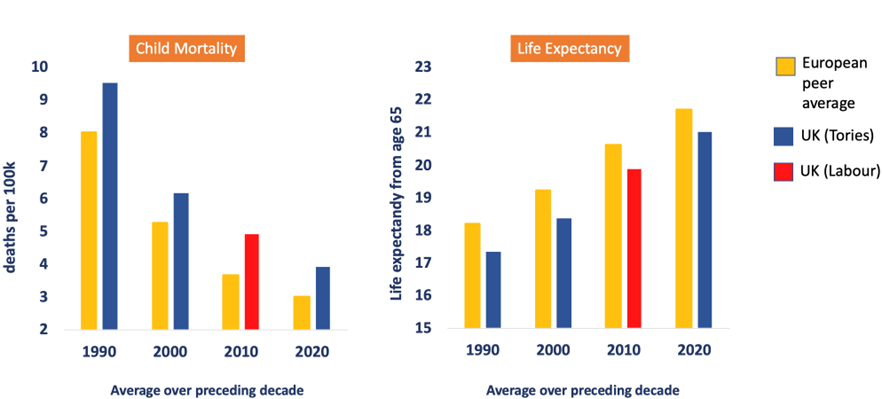

6. In addition to overwhelming domination, FPTP allowed the Tories to indulge far greater policy extremes – FPTP has consistently permitted the Tories party to apply far more strident forms of neo-liberalism than European PR peers, including materially lower investment levels in public services as per below. Long term, Tory domination has normalised their radical right-wing stance among voters to the extent that the Labour party, with 3 huge majorities, was unable to even match spending levels of its mostly centre-right, European PR peers. In short, FPTP makes British politics a lot more American than European…

7. 4 decades of government with little or no influence from other parties have come at a cost – and so it is no surprise that consistently lower levels of public investment have resulted in a poorer quality of life for voters in the UK when compared to European peers; child mortality and life expectancy outcomes lagged European peers in each of the 4 decades under review with even the 13 year spell under the Labour party unable to buck the under-performing trend v European PR peers.

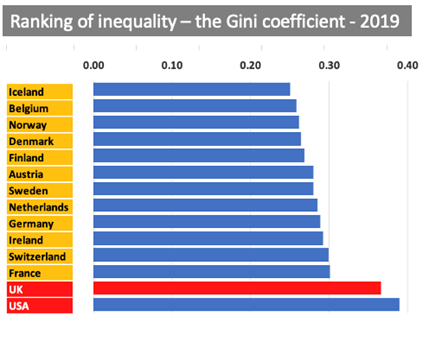

- With no means to stop and reverse inequality, FPTP leaves the UK trapped in a downward spiral – the Gini coefficient below is the standard measure of how equally dispersed income is across a country; a score of 1 means one person (or family) has all the income, a score of 0 means perfect equality is achieved across all in society. The most equal countries in the world are those at the top of the table, with scores of around 0.25. But FPTP states in red are at the bottom with inequality scores far in excess of the equality leaders, our European peers. The two most unequal countries are the ones that have suffered the two greatest populist shocks in recent times – Brexit and Trump. This, it seems, is what we can expect when inequality gets out of control. There may be more shocks to come but FPTP appears to have no means of doing anything about it…

In light of the clear evidence underlining the harmfulness of FPTP, you’d expect that reforming the voting system would be a priority for the two dominant UK parties. But it isn’t and probably won’t ever be. They know that changing the system would mean the end of single party majority rule, the end of the duopoly they’ve benefited from for decades and most likely, the break-up of their parties to boot.

This clip from the campaign group Led by Donkeys show how the Labour leader Keir Starmer abandoned his earlier commitment to reform the UK electoral law, despite the clear mandate of his own party conference.

But Scotland can choose a different path; it is already 25 years along its Proportional Representation journey under devolution and with every year, every election that goes past, the culture of compromise, of coalition, of normal European politics, beds into life in Scotland too. Given the ever higher risks now posed by FPTP in the UK, Scotland’s European PR path may well come to define its longer term destiny.

Stuart Donald

To get in touch with Stuart and find all details about his in depth research, you can find all material and contacts on his website: www.sdonald4pr.com.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Arguably, Australia has more than 2 parties alternating in government, but the 3 main parties forming the Liberal / National coalition arrangement that forms the conservative governments, has operated predictably as a single party when the coalition gets elected to government for many decades; in practice, this creates a two-party system (the progressive party, the Labor party, is constituted as a single political party). NB the 2 other FPTP countries inherited the system since it was in force when they achieved independence from the British Empire.

[2] An average of 42% of votes and 55% of seats across the 8 GEs the Tories have won since 1979

[3] Strictly speaking, the Tories have won 7/11 with the 8th a coalition with the Libdems. However, the Tories dominated the arrangement being by far the largest party, driving through a conventionally Tory policy agenda including Europe’s most extreme austerity program.