On the 4th of July 2024 we witnessed the most dysfunctional general election in UK history.

As widely expected, also by us, Keir Starmer’s Labour won the elections by a landslide, gaining 412 seats, almost 300 more than the Tories – the widest distance that any UK government has had from the official opposition since the national unity government that emerged from the 1931 elections, following the 1929 financial crisis.

The end of 14 years of Tory government in the UK are surely to be celebrated around Europe, as they brought austerity, Brexit, constitutional crises, scandals, and one of the worst responses to the pandemic in Europe. A dark era of British politics has come to an end, and a new phase that promises to be structurally different begins. For all this, Europeans can rejoice.

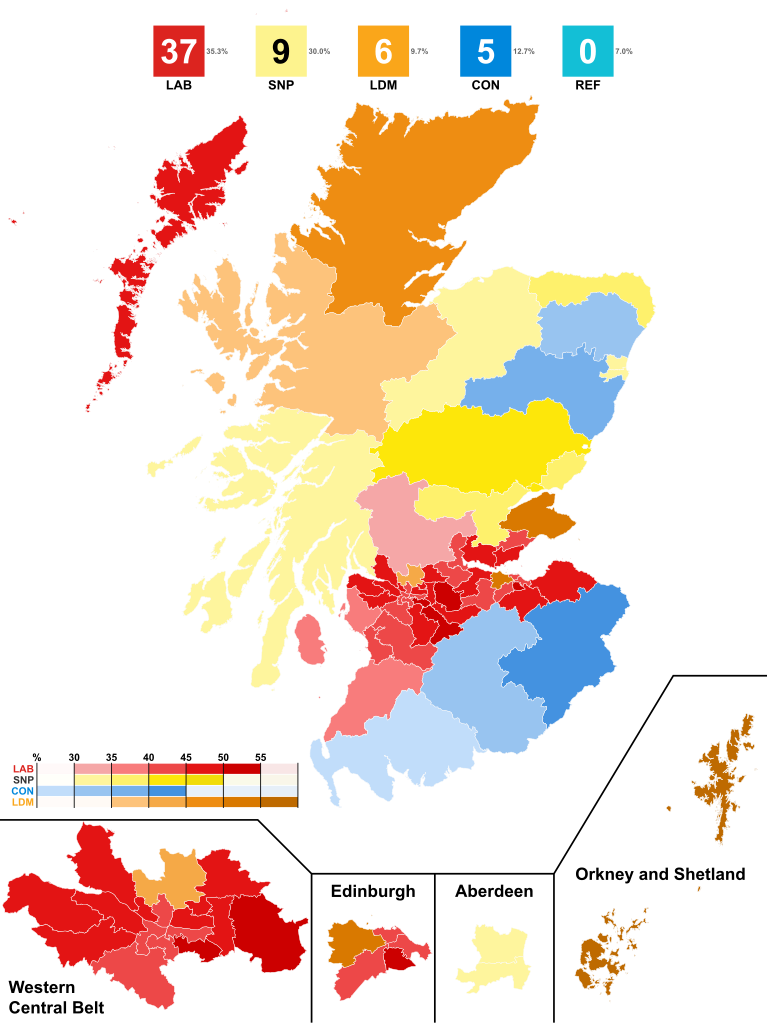

The vote in Scotland also delivered a clear victory for Labour. The SNP losing a third of their votes compared to 2019 and remaining with just 9 seats means that there are many considerations to be made in the independence movement (which still polls at 50%, more on this below) as the referendum is pushed further into the future.

But are these really the only conclusions to draw from these elections? We don’t think so.

A democracy which has never been so dysfunctional

With 23,7% of the votes cast, the Tories had the worst result in their political history. Historians wondered about the century in which they did worse. On election night, for a while the BBC’s focus was on the 1832 election but Rishi Sunak’s 121 seats still pale in contrast with the 175 gained by the Duke of Wellington – although perhaps he is now best remembered in Scotland for the traffic cone that sits on top of his statue in Glasgow.

The statue of the Duke of Wellington, who got more seats than Rishi Sunak

However, such a poor result for the Tories was not due to a very strong show of support for their opponents but rather the fall in their own vote. Turnout sank in sync with the Tory vote (particularly in the areas which voted Brexit by the highest margins) to the lowest in the history of universal suffrage elections in the UK, at around 52% when considering also those who didn’t register to vote.

Despite such low turnout, the main opposition share of votes was just 33,7%. In other words, the Labour Party had the lowest share of votes of any party winning government in UK history. Yet, thanks to the democratic and social injustice of the First Past the Post electoral system, Labour doubled their votes to get 66% of the seats. Never in history has a party taken so many seats with so few votes: 9.7 million votes.

This is far less than the 13,5 millions votes (43,2%) that Blair’s Labour won in 1997 or of the 12.8 million votes (40%) the party secured in 2017, when Jeremy Corbyn was leader, less even than the 10.2 million Corbyn’s Labour won in 2019, when, according to Starmer, Labour had “a devastating result”. Only at the third electoral victory of Tony Blair, in 2005, Labour got slightly less votes, 9,6 million, due to the disillusionment of many progressive voters following the Labour led invasion of Iraq.

Polling expert John Curtice explained how Starmer’s victory “was not so much due to a rise in support for the party, but “largely on the back of a dramatic 20-point decline in Conservative support”.

Keir Stamer has unprecedented level of unpopularity

Indeed there is even some evidence that Labour actually lost votes during the electoral campaign itself perhaps thanks to Starmer’s unpopular remark that rejoining the EU won’t happen in his lifetime.

And what about the Labour leader’s personal performance at his own Holborn and St. Pancras constituency, in central London? Keir Starmer lost almost half of his votes from the last election, falling from 36,641 to 18,884 thanks to the excellent result from an independent candidate expressing a protest against his choices on Gaza.

To our knowledge, Starmer’s disastrous personal result is completely unprecedented in British political history. Since the introduction of universal suffrage, candidates who then become prime minister all have experienced massive gain in votes in their own constituency, mostly due to the increase in prestige and popularity when they are on the verge of gaining power.

To give you a few examples, Clement Attlee gained 17,3% in his Limehouse constituency in the 1945 general election, Margaret Thatcher increased her share of votes by 8,5% in Finchley in 1979, Tony Blair by 10,7% in Sedgefield in 1997. Compare this against the dramatic -17,4% of Starmer. One gets a sense of a Prime Minister who, just a few weeks after entering Downing Street, has an incredibly deep level of unpopularity, arguably the most unpopular new Prime Minister the UK has ever had.

This unpopularity naturally drove Labour losing metropolitan seats in Bristol, to the Greens, and, in in Birmingham, Leicester, Blackburn and West Yorkshire to four independent candidates that had stood on pro-Palestine platforms, as well as the victory of Jeremy Corbyn, re-elected in his Islington North constituency, his first as an independent after being kicked out from Labour.

Other independents came a close second or third. Labour’s new health secretary, Wes Streeting, won his London seat by 500 votes. In a nearby constituency, Labour lost the seat after ditching its popular progressive local candidate.

These results from England speak about a Prime Minister that doesn’t seem to command the trust of many people there. Indeed Oliver Eagleton, one of his biographers, described him on the New York Times as having “a deeply authoritarian impulse, acting on behalf of the powerful”, not the most appealing trait for a progressive or democratic leader.

Certainly this description appears consistent with the suspension of 7 Labour MPs who voted in favor of an SNP amendment to scrap the cap introduced by the Tories on the number of children for which a family can claim a benefit, a cap known to prevent reducing child poverty.

Indeed it is possible that none of this mattered too much as any Labour Party, with any program and any leader, simply by retaining its voters, would have won by a landslide with this electoral system against these Tories, in the first elections post-Brexit, a project that fewer and fewer people are willing to defend, let alone support.

Obviously Boris Johnson’s scandals and the collapse of the pound during the very short premiership of Liz Truss, who lost her seat, contributed to the devastating collapse of the Tories.

Starmer, if possible, reduced the size of this avalanche in terms of the number of votes, and perhaps increased it slightly by distributing them better among the seats.

But it remains true that a democratic system that distributes seats so unevenly is untenable and must be reformed. If it ever made sense for a country when Labour and the Tories monopolized the electorate, it doesn’t anymore now that the combined share of the vote for the two biggest parties was the lowest level since the two-party system began.

The UK is a multiparty system with a electoral law tailored for just two

Despite the FPTB being designed for two parties systems, even England is now clearly a multiparty system with 4 parties polling above 10%: Labour (33.7%), the Tories (23.7%), the Liberal democrats (12.2%) and Reform (14.3%), the new party of Nigel Farage, elected to Parliament for the very first time (at his eight attempt).

Among the other parties, the Liberal Democrats achieved the best result in a century (72 seats) without any significant increase in votes, again under the first past the post it is sufficient for your opponent to fall. They will however have much more space in Parliament and have a chance of growing as the main pro-European opposition to Starmer’s keep-calm-and-carry-Brexit-on government.

The Greens quadrupled their seats to 4, winning 7%, an incredible percentage for such a small number of seats and a party protesting against inaction on climate change. But a protest that will most likely grow if the Starmer government confirms he doesn’t want to step up its commitment to the ecological transition that has massively downscaled since his campaign to become Labor leader 4 years ago.

Where the democratic injustice of the FPTP was more blatant was however, with the 5 seats obtained by Nigel Farage Reform party with more than 4 millions votes, almost all, former Brexit and Tory supporters. Labour had slightly more than double their votes but as many as 100 times more MPs.

On top of the democratic injustice it’s worth noting that Reform candidates came second in about a hundred of seats in the Midlands, in the north of England and in Wales. The parliamentary spotlight alongside the annihilated Tories offers Farage a once-in-a-lifetime chance to try to oust the Conservative Party as the main right-wing opposition and, however ominous a prospect, a return of Trump to the White House could open the doors to a challenge to Starmer in a few years.

We don’t agree with anything that Farage’s anti-immigration, anti-European, populist pro-Putin party expresses. But from our perspective these electoral results make a compelling argument for electoral reform. No complacency is possible with a character who has already demonstrated that he knows how to change the history of the UK for the worse.

Yet it is astonishing that discussions around electoral reform remain completely absent from the UK debate, both before and after the election.

Labour King’s Speech fell short on democracy

When the new Labour government has presented their program in the archaic procedure which goes under the name of the “King’s Speech”, where the unelected monarch reads out the list of provisions that “his” government plans to implement, alongside a program of state interventions whose success is not guaranteed (including the nationalization of railways in England – the Scottish government had already done so a few years ago) it was notable the lack of serious democratic and constitutional reform.

Not only electoral reform was not contemplated. Even the commitment on reducing the voting age to 16 which was announced in the Labour manifesto with great fanfare, and which would have harmonized the voting age between England and Scotland, was scrapped unceremoniously.

Reform of the unelected House of Lords was downscaled again to just the abolition of the hereditary peer, after being deemed “immediate and essential” in the Labour manifesto and whose abolition was promised by Starmer when elected Labour leader. Indeed the “king’s speech” was delivered precisely there, in such outdated and frankly ridiculous pomp and pageantry.

Somewhat more sensible are the proposed English devolution bill, which will grant more powers to metropolitan majors, but that will not address the issue of England’s representation, and the plan for a new Council of the UK and of its Nations and Regions which would allow the first minister of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to meet every few months together with the UK prime minister and England combined or local authorities. From the perspective of the Scottish First minister it is certainly better being consulted than not, but there is still no guarantee of being listened to and we will need to see how the government plan will be implemented.

No provision is there to respect decisions of the devolved assemblies and the fact that Starmer supported disgraced Welsh leader Vaughan Gething when he had already lost the confidence of the Welsh Assembly doesn’t speak for great respect for devolved assemblies.

Lastly and more worryingly from our perspective, the new government stance on immigration appears to be relatively unchanged from the previous one. Yes the awful and never actioned Rwanda scheme has been scrapped but deportations of migrants who have seen their application for asylum rejected have already begun to rise and plans are for them to rise further, as announced by the new Home Secretary Yvette Cooper on the Sun newspaper.

What does it all mean for Scotland?

In Scotland a completely different political dynamic was at play. Labour increased its share of votes benefitting from the simultaneous collapse of the Tories and SNP. About a third of the pro-independence electorate did not vote, partly discouraged by the inability of the SNP to obtain a new referendum, partly voted Labour “to kick out the Tories”, thus allowing it to win about forty more seats (it started from one!).

The SNP has certainly paid for a decline in popularity after 17 years of complete domination of Scottish politics, partly due to the exit of Nicola Sturgeon and a credit offered to the first Labor Prime Minister for fifteen years.

This analysis by Adam Ramsay explores some of the reasons behind the defeat of the SNP, reduced to 9 seats, including the broad difference between Scottish and UK election as well as the cost of breaking the coalition agreement with the Greens and more.

From our standpoint we want to highlight the absurdity to label as an absolute failure the results of the SNP, which obtained 30.0% of the share of votes in Scotland, while at the same time celebrating the astounding success of Labour, 33.7% across the UK. And we would also stress the fact that very different political dynamics were at play across the UK, including in Northern Ireland, where Sinn Féin was coming first for the first time in history.

What we can reassure our readers in Europe is that the debate over Scotland’s desire to rejoin the EU as an independent country is not going away. Scottish polls this summer have ‘yes’ to independence ranging from 46% to 51% in favour. With a clear majority in favour amongst young people, the argument is definitely continuing.